Perhaps I was a bit giddy. It was the night of the Super Bowl and my oldest son had just returned from a party. He was showing us a video of a “Kosher Halftime show”, and it was quite amusing. We heard a knock at the door.

It was someone collecting Tzeddakah. His frock and his wide brimmed hat hinted that he was a Yerushalmi. Our visitor looked about my age. His brow was furrowed. His longish beard was streaked with gray and his eyes had a strong, piercing quality to them. His green card – I always ask to see one – identified him as a Chashuve Avrech, with 13 children and Chassunos to make. I reached into an envelope, in which I keep Tzeddakah money, and placed in his hand a modest sum. He paused and asked in Hebrew “Can you give me more?”

Usually, when I am asked this question, I respond firmly, but gently, that this is what I can give. Tonight, though, I found myself saying in my imperfect conversational Hebrew “You know, I too hope to make Chassunos. Perhaps you can give me some money.” Our visitor was taken aback for a moment, but then he reached into his wallet and offered me substantially larger sum than I had placed in his hands. I laughed. He didn’t.

The Avrech let me know, in measured tones, that, in his neighborhood, when people are collecting for a wedding, this is the standard amount he gives them. “In fact,” he informed me “had you come knocking at my door, I’d have offered you the same.” There were hurt and disappointment in his eyes.

∞

Over, the years, I’ve come across my fair share of people whom I consider entitled. There are collectors who believe that most every American Ba’al Habayis is so wealthy, he doesn’t even know what to do with it all his money. Frankly, I feel resentful when people who allow themselves to learn full time, well past middle age expect me to contribute to an apartment for their children. This, when I, who work long hours 6 days a week, am unsure how I will cover my children’s wedding expenses. I even question the right of many such people to underreport their own income, take government funding for all their children and, thereby, enjoy the benefits of living in a country where others pay huge amounts of tax to support them.

This particular man was, in all likelihood, offering me money for which he had not worked. Other people had earned it and generously given it to him to pay for his children’s weddings; he was now passing it on to me, as though it were Monopoly money. I even began to question, in my mind, the term “Avrech” – young man. Could we truly call this man in his 50’s an Avrech?

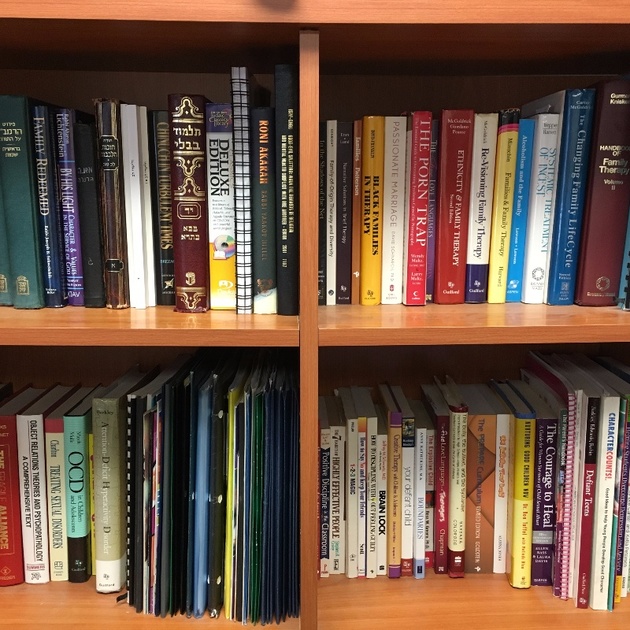

That being said, I sensed in my visitor a certain spiritual potency. Avrech or not, something about the way he carried himself told me that he was living his life almost exactly as his Rebbeim had taught him to live it. In all likelihood, his family is more excited about Sifrei Kodesh than the Super Bowl; they are more dialed in to Halachah than Halftime. This Avrech was someone who recognized that the only thing that is totally in his hands is his spiritual and religious choices; Parnassah sometimes comes and sometimes it doesn’t.

I also began to look at myself. Do I sometimes become arrogant about my own capacity to earn a living? Do I forget the extent to which Hashem enters into the equation?

Digging deeper, I began to recall how the real professional opportunities of my life did not begin to materialize until I had resumed setting aside a daily sum for the sake of Tzeddakah. Tzeddakah is typically defined as charity, but perhaps it is more accurately defined as righteousness and fairness. We are taught, homiletically, from the verse Es He’uni Imach that part of the money that comes our way is not meant for us. Rather it is being placed in our safekeeping. Ultimately, it belongs to the Uni –the person in need.

I began to wonder, Super Bowl-related giddiness aside, whether there is a larger pattern present when I cross the boundary of Tzeddakah collectors, as I did tonight. Am I somehow finding myself being caught between feeling unfairly pressured and between recognizing that I could live on less and, thus, give more? Might I even be feeling that, in some way, I am a failure, because I am not that American guy who has extra twenty dollar bills oozing out of his every pore?

I, of course, did not take the money he offered, but I also did not increase my donation. At the end of day, I was not convinced that my visitor had a right to receive a larger share of my Tzeddakah money. Even the values of piety and Bitachon, which he’s “nailed”, do not cancel out the values of fiscal Achrayus and teaching one’s child a profession, which he’s (apparently) failed. Besides, I’ve committed a significant share of my Tzeddakah to a particular family that is more closely related to me than he is.

Then again the values by which I’ve chosen to live my life do not cancel out his values – ones that he approaches with internal consistency. I was, as such, no longer feeling all that clever about reversing things and asking him for money. The smile on my lips had, by now, faded. “Yitachain, She’atah Tzodek/perhaps you are right, at least partially so,” was the thought that my mind sent in his direction. I half hope, half believe that he noticed this in my softened features. He left the house and continued on his way. I gently closed the door.

As I rejoined my children, more than one of them wondered, “Why were the two of you talking for so long?” I couldn’t exactly lay out all the pieces for them, certainly not with the remainder of the Halftime show beckoning. I did say, partly to them, partly to myself, “Next time a collector asks me for more money than I’ve offered, I will be more protective of his dignity. I will not make a joke at his expense, and I will certainly try not to shame him.”

Glossary of terms:

Achrayus: Reponsibility

Ba’al Habayis: Working man (lit. Homeowner)

Bitachon: Trust (in G-d)

Chashuveh Avrech: Prominent (young) full time student of the Talmud

Chassunos: Weddings

Es Ha’ani Imach: The poor person among you

Halachah: Jewish law

Hashem: G-d

Parnassah: (wherewithal to achieve) physical support

Rebbeim: Spiritual teachers, mentors

Sifrei Kodesh: Holy books

Tzeddakah Charity

Yerushalmi: Jew who lives in Jerusalem and is typically descended of several generations who have done so

Previous

Previous